Research

Wu Ecological and Evolutionary Physiology Lab

FRAMEWORK

Our research integrates physiological principles with ecological and evolutionary theory to understand how species respond to environmental and anthropogenic change across space and time. We combine experiments, field observations, data synthesis with simulation-based and statistical models to develop causal models that can help inform conservation practices.

Some example research that incorporate this framework include:

APPROACH

EXPERIMENTAL

We use experimental approaches to examine a range from physiological, behavioural, and developmental response. Experiments allow us to tease out cause-and-effect relationships under controlled conditions which are important for developing causal models and a mechanistic understanding.

Example research:

FIELD-BASED

Data from free-ranging animals and their habitat provides important information on how animals work in the real-world and allow experiments to be validated under ecologically-relevant conditions.

Example research:

COMPARATIVE & SYNTHESIS

We incorporate 'big data' synthesis to understand broad-scale ecological and evolutionary patterns. We also use meta-analytic approaches to reveal commonalities, differences, and bias in studies that ask similar questions.

Example research:

- •Size-reproductive scaling relationship

- •Physiology explains dispersal and activity

- •Sublethal effects of UV radiation

SIMULATION-BASED

Beyond traditional statistical approaches for modelling biological trends, we also use mechanistic models to understand nonlinear, complex phenomena based on explicit processes. For example, biophysical models can be used to calculate an organism's body temperature given its surrounding microclimate and its traits to predict yearly activity, phenology, energy use, and survival.

Example Research

Emerging Infectious Disease & Australian Wildlife

Infectious diseases are a growing threat for biodiversity worldwide. Given their negative ecological and socioeconomic repercussions, it is crucial to predict the likely exposure and sensitivity of populations to the global spread of pathogens.

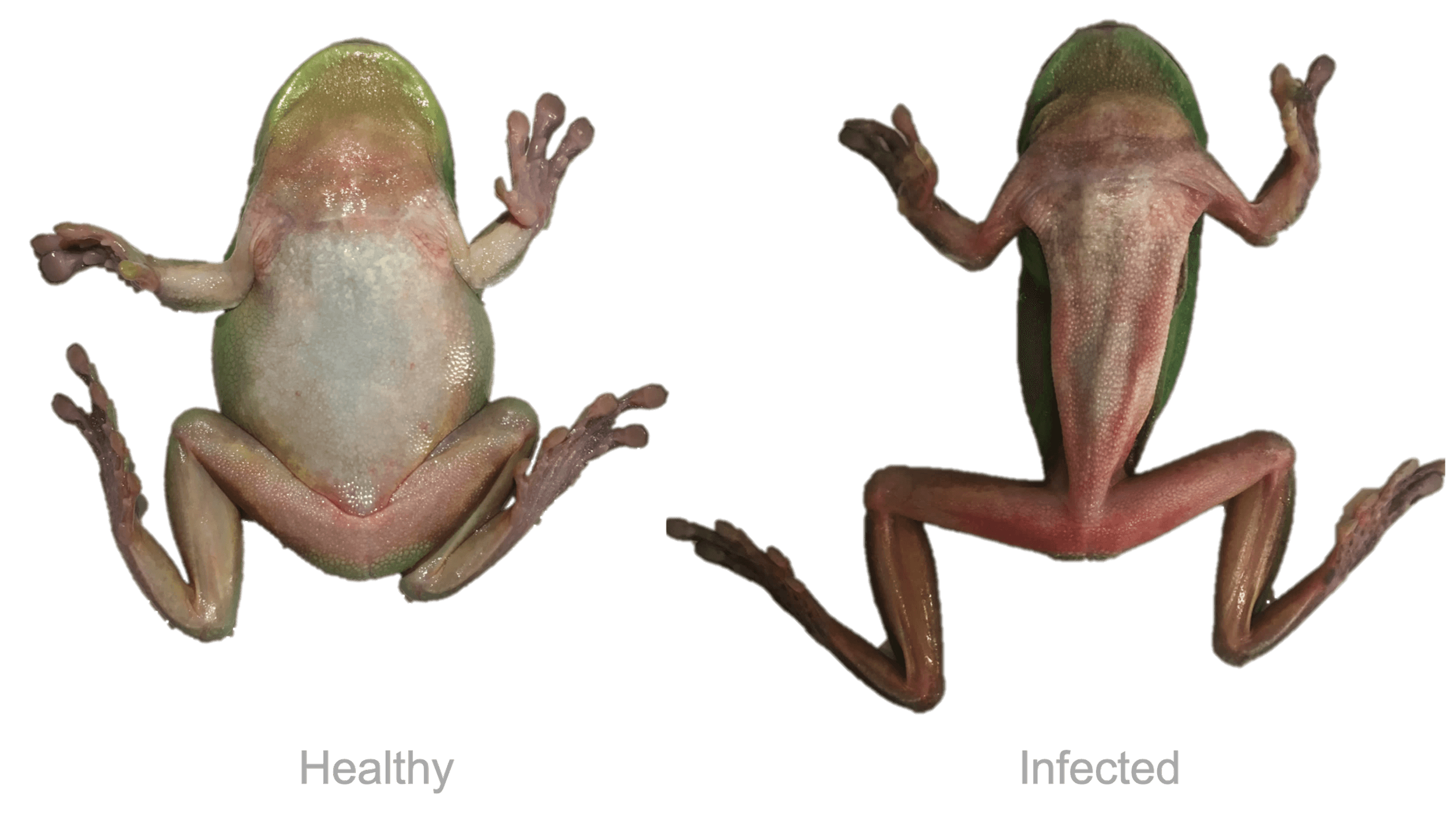

Chytridiomycosis

This work contributed to understanding how a lethal fungal disease, responsible for the largest loss of vertebrate biodiversity from a single disease, causes mortality in amphibians by examining disruption at the site of colonisation—the skin. We explicitly linked how the disease altered molecular and cellular processes relating to skin function [1, 2, 3], and smaller infected frogs have higher physiological costs, which may explain size-specific mortalities observed in the wild [4]. Our work helped to understand the causal mechanisms for how frogs die from this disease, while also highlighting the role of physiological approaches to understanding ecological threats [5]

White-nose syndrome

This disease affects hibernating cave-roosting bats, and has killed millions across North America since its introduction in 2007. There is concern that if the fungus is introduced to Australia, WNS could pose similar threats to our native bats. Predicting the vulnerability of Australian cave-roosting bats to WNS is difficult because of scant knowledge of their winter biology [6]. We find 90% of winter hibernation caves had microclimates suitable for the fungus to grow, and the winter fat use and torpor patterns of our bats are compatible to North American cave-roosting bats in similar climates [7]. Our research suggests that Australian cave-roosting bats are at high risk of being infected by the fungus that causes WNS.

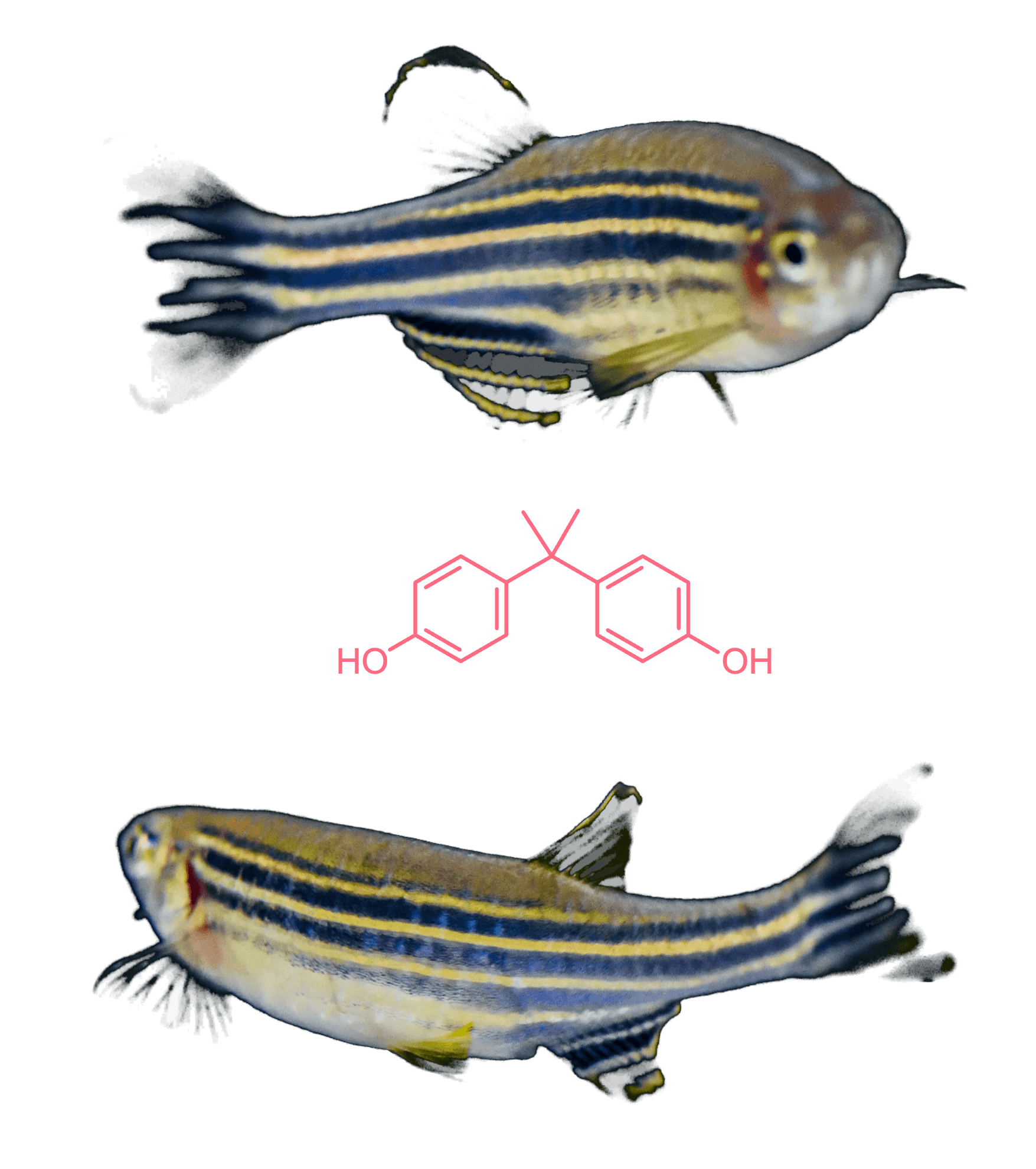

Plastic Pollution & Climate Change

Plastic pollution is a monumental global environmental and health problem, and Australia has one of the highest exposures to bisphenol A (BPA), a plastic leachate.

We show that BPA exposure, which now represents a novel environmental driver, has a widespread impact on aquatic organisms across the literature [1]. Using experimental approaches, we show BPA exposure at ecologically relevant concentrations can disrupt the thermal responses of swimming performance of adult fish [2], and the energetic cost of growth of juvenile fish [3]

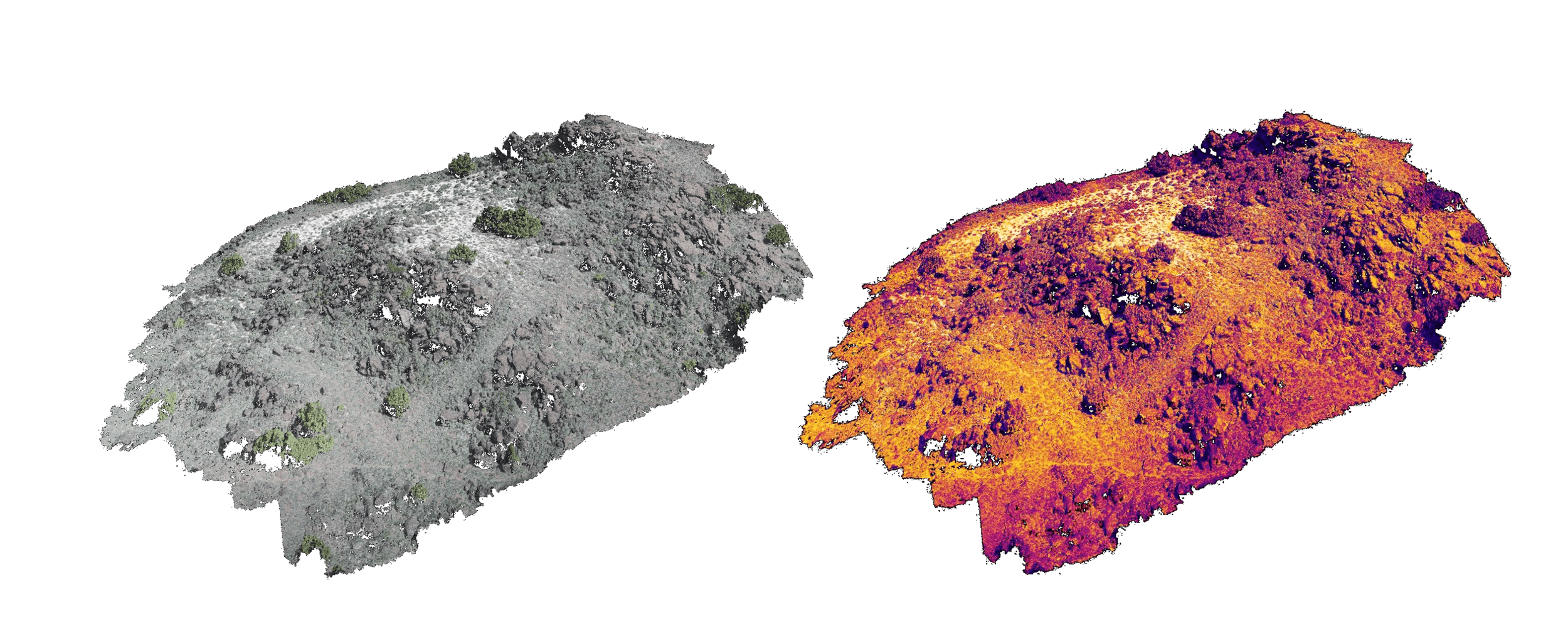

Microclimates & Climate Change

Realistic predictions of how animals will respond to and survive climate change require a detailed understanding of how animals interact with their microclimate.

Microclimates can buffer the effects of climate change by creating localised conditions that reduce temperature extremes, retain moisture, and provide thermal refugia for species and raising young. Some example research around this theme include the effects of sand substrate and temperature on burrowing energetics [1] and burrow use [2] of lizards, how shaded habitats influence the thermoregulation of snakes [3], and predicting warming risk [4, 5] and drying risk of amphibians [6] using mechanistic models.

Curiosity-Driven Research

We also use curiosity-driven research to better understand ecological and evolutionary patterns observed in nature.

- 1How agamid lizards are able to achieve running on two-legs with implications for robotic designs [1]

- 2If tuatara are able to discriminate scent from within and/or between populations [2]

- 3How does size-scaling relationships influence the reproductive output and population trajectories of sea turtles [3]

- 4Does physiology explain individual-variation in activity, dispersal, and exploration [4]

Interested in Our Research?

Explore our publications for detailed findings or join our team to contribute to these research areas.